Start your journey

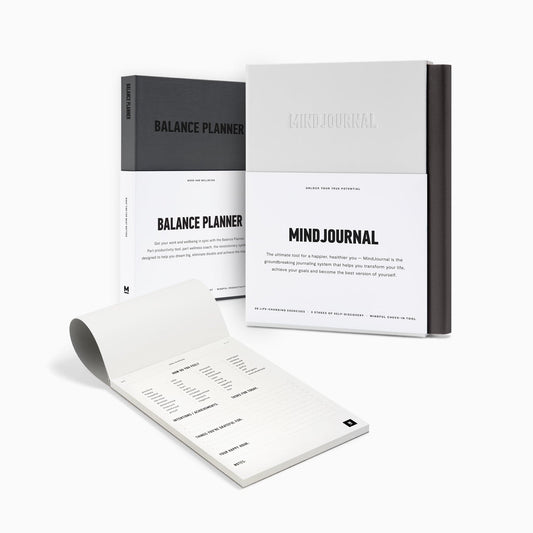

Browse our bestsellers for a better you.

Frequently added:

by MindJournal – 4 min read

You’ll likely already have heard the term post-traumatic stress disorder, or ‘PTSD’ for short. It’s the clinical term for what was dubbed ‘shell shock’ back in World War I and refers to the mental scarring that can occur after a person suffers a devastating experience.

These days we know that instead of being limited to military combat, PTSD can be triggered by a range of life events. Several recent studies even suggest that the pandemic — with all the social isolation, unemployment, even grief — may have caused a spike in PTSD cases. And yet, some professionals think trauma can actually be, well, good for us.

Enter ‘post-traumatic growth.’

The term was coined in the 1990s by psychology professor Richard Tedeschi, PhD, and his colleague Lawrence Calhoun, PhD, to describe the idea that some people not only recover from adversity, but in some ways, become better for it.

A kind of flip-side to PTSD, the theory is that trauma can be the catalyst for positive change, typically in five areas: appreciation for life, relationships with others, recognition of new possibilities, personal strength, and spiritual change.

“It’s not ‘what’s wrong with you?’ but ‘what happened to you?’, and what opportunity is there to use that."

Of course, nobody is suggesting you should seek out trauma in order to experience PTG. Still, the idea is re-working how some professionals look at stress and our ability to use it for good. To not just ‘bounce back’, but ‘bounce forward’.

“Our studies suggest quite a different perspective on responding to trauma,” says Dr Tedeschi. “Different to the traditional medical approach that diagnoses a disorder, that sees the individual as sick or broken.

“It’s not ‘what’s wrong with you?’ but ‘what happened to you?’, and what opportunity is there to use that to propel the individual into another phase of life, to work out who they’re going to be in the aftermath of the trauma,” adds Dr Tedeschi.

He’s not alone. In 2017 the American Medical Association called for new approaches to helping those with PTSD, moving away from the encouragement for sufferers to accept their ‘new normal’, often aided by prescription drugs.

There’s even real-world evidence of PTG in action. Quite literally, in the case of Ken Falke, an ex-US Navy man and Gulf War veteran.

During a military parachuting operation, Falke suffered from a broken back in two places, a dislocated shoulder, and was knocked unconscious, resulting in a severe concussion. After the incident, Falke was told that his military career was over.

During recovery, Falke discovered that he didn’t find the conventional ways by which the authorities dealt with his trauma helpful – nor, he observed, did many other service members who witnessed, or were involved in, real nightmare stuff.

With renewed purpose and motivation from his experience, he launched the Boulder Crest Foundation, a non-profit recovery retreat for veterans which has since had over 1,000 servicemen go through its PTG programme.

“There’s an opportunity to thrive after trauma if you do the right things,” reckons Falke. “It’s just about the right training. And people, after all, are the sum of their training.”

Indeed, anyone who is familiar with the story of how MindJournal came to be will also know that it too was also founded out of tragic circumstances.

Granted, not everyone experiences post-traumatic growth. “It’s not inevitable,” stresses Tedeschi. “But we should be looking to facilitate something that can be a naturally occurring event in the right conditions.”

To facilitate your own post-traumatic growth, here are a few strategies you can practice.